Catalogue Note Sotheby's After the Prom appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on May 25, 1957

Catalogue Note Sotheby's

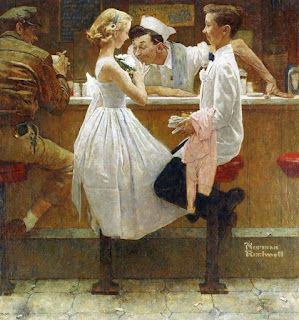

After the Prom appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on May 25, 1957 and has endured as one of the artist’s most recognizable and beloved images.

The scene depicts two teenagers sitting at the counter of a typical diner. Still dressed in their formal attire, the couple has just arrived from their junior high school prom, and their faces clearly still resonate with the excitement and significance of the evening.

The young man sits and watches proudly as his beautiful date flaunts the corsage he has given her to the soda jerk behind the counter. He leans in eagerly to inhale the scent of the delicate flower. A uniformed worker sits to their immediate left. He watches the scene as it unfolds and smiles knowingly to himself, as if remembering his own experience of first love and the emotions it induced.

Images of young love and courtship pervade Rockwell’s body of work, even from the earliest years of his career (Fig. 1). In the late 1950s, the subject inspired several more Post covers, perhaps prompted by his son Peter’s decision to marry his childhood sweetheart. By the onset of this period, Rockwell’s Post covers had achieved a pervasive level of popularity, yet the artist saw even greater levels of creativity and professional success as the decade progressed.

Rockwell painted an astounding 41 Post covers during the 1950s. Technically, he pushed himself farther than ever before, designing his most ambitious compositions and experimenting with innovative materials and techniques. Thematically, he sought to portray imagery that was more explicitly American in character, capturing people living their everyday lives and creating scenes that had the possibility of occurring in any town or home.

Although he reacted to the changing social realities of Postwar America, Rockwell’s defining sense of idealism remained resolutely intact. The publication of each Post cover seemed to outdo the last as again and again the artist presented the country with imaginative images that spoke to the concerns of its present yet were steeped in the traditional values of its past.

In his classic manner, Rockwell presents a scene in After the Prom that is simple in subject yet extraordinarily complex in emotional content and compositional structure. Indeed, Rockwell derived the composition of After the Prom through a complex synthesis of photography, references to the Old Masters and his own seemingly limitless imagination.

Rockwell designed the basic structure of After the Prom using a set built in his studio on Main Street in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he moved in 1953. Seeking the degree of authenticity his best works required, he borrowed two stools from an actual diner. Encouraged by a younger generation of illustrators that included Steven Dohanos and John Falter, Rockwell began to use photography to assist in composing his paintings in 1937.

He typically started his process by sketching the scene as he imagined it. Only after painstakingly collecting the appropriate props, choosing his desired models and scouting locations would photography sessions begin in his studio. Rockwell rarely took these photographs himself, however, preferring to be free to adjust each element while a hired photographer captured the shots under his direction.

He initially posed his friend David Loveless in the role of the soda jerk but felt unsatisfied with the facial expression captured by photograph. A consummate perfectionist, Rockwell decided to retain the distinctive positioning of Loveless’ arms but replaced his face with that of his assistant, Louie Lamone, who was able to achieve the more humorous look the artist wanted.

Rockwell recognized the benefits that came from utilizing the camera, later articulating, “I feel that I get a more spontaneous expression and a wider choice of expressions with the assistance of the camera and I save a lot of wear and tear on myself and the model” (Rockwell on Rockwell: How I Make a Picture, New York, 1979, p. 92).

Although photography was an integral component of Rockwell’s technical process—he typically used fifty to one hundred photographs for his most sophisticated compositions—a completed painting was rarely an exact transcription of a single shot (Figs. 2 and 3). “I do not work from any single photograph exclusively,” Rockwell stated of his methods, “but select parts from several poses, so my picture which results from photographs is a composite of many of them” (Ron Schick, Norman Rockwell:

Behind the Camera, 2009, p. 101). Paintings like After the Prom demonstrate the artist’s undeniable inventiveness and sophisticated understanding of compositional design that allowed him to create his iconic images of American life, scenes that immediately transport us back to an earlier time and place, yet somehow simultaneously remain absolutely applicable to the present.

Rockwell enjoyed making reference to other works of art within his own paintings, particularly in this period. This device provided the type of visual game the artist loved to present his viewers with, but Rockwell also used these allusions to demonstrate the extent of his knowledge of art historical precedents.

The positioning of the central figures—the couple and the soda jerk—form the three sides of an inverted pyramid, mimicking the configuration often utilized by the painters of the Italian Renaissance and creating the impression of stability within the composition. The strong horizontality of the counter and the patterning of the floor is countered by the vertical elements of the stools and the figures themselves, creating a geometric grid into which he inserts the figural elements in a pattern of precise forty-five degree angles.

This arrangement contributes to the flawless balance of the scene. In addition to enhancing the sense of depth within the two-dimensional picture plane, the older figure on the left serves as, “a character within the painting’s space whose response to the action we may take as a cue to our own response and through whose eyes we are presumed to see the scene portrayed in its optimum configuration” (Dave Hickey, “The Kids Are Alright: After the Prom,” Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, New York, 1999, p. 119).

As Hickey notes, this decision references a technique of 18th century French painting as exemplified by Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s, The Swing, in which the man lounging in the bushes has a revealing view of the woman in the swing that the viewer is not granted, yet we know from his expression and reaction that the tone of the work is intentionally humorous (Fig. 4).

In a similar manner, Rockwell emphasizes the dreamy and romantic mood of After the Prom in several ways. Much of the painting displays the palette of more subdued colors typical of his work at this time but he renders the central figures in brighter shades of white and light pink.

This decision immediately draws the viewer’s eye to the primary action of the scene while also seemingly bathing the couple in a tangible glow. Rockwell depicts the figures and such details as the dangling keys and pencils stored in the man’s back pocket with a near photographic realism.

This contrasts dynamically with the more expressive application of paint he uses to render elements such as the floor and background of the diner, in which he layers subtle tones of red, green and blue within the overriding shade of brown. He replicates fabrics with a similar treatment: the girl’s white dress is composed with touches of cool blue to indicate its delicate folds, capturing the three-dimensionality of the diaphanous fabric.

Rockwell places the counter and stools of the diner at a point above the middle of the picture plane, creating the sense that we as the viewers are standing in the room, watching the scene unfold as well. The subtle yet highly realistic details he includes such as the girl’s pink sweater her date sweetly holds and the witness enjoying a cup of coffee in the evening suggest that here Rockwell presents only one moment of a larger overarching narrative, in which preceding and subsequent events are visually implied.

He, “gives us the happy ending to the story, but we must reconstruct for ourselves the events which led up to it” (Dr. Donald R. Stoltz and Marshall L. Stoltz, Norman Rockwell and ‘The Saturday Evening Post:’ The Later Years, 1943-1971, New York, 1976, p. 157). In viewing the painting, we are at once transported to a warm spring evening and encouraged to remember and re-experience our own memories of youthful love.

Of the first 310 Post covers Rockwell painted between 1916 and 1960, 306 portray ordinary people, a statistic that attests to the artist’s desire to visualize the everyday moments typical of the human experience. This creative intent lies at the core of Rockwell’s almost universal accessibility and familiarity: even if the precise moment he depicts has not been experienced, the feeling he conjures almost certainly has.

We view his images of a parent sharing the facts of life; of young couples applying for a marriage license; of a boy leaving home for the first time, and we instinctively recall instants of our own lives (Figs. 5 and 6). Although the scene Rockwell depicted in After the Prom may be a quintessentially American milestone, the discovery of adolescent romance is an unforgettable experience shared by nearly everyone.

Norman Rockwell (American painter and illustrator) 1894 - 1978

After the Prom, 1957

oil on canvas

79.1 x 74 cm. (31.13 x 29.13 in.)

private collection

© photo Sotheby's

Comments

Post a Comment