Buck Ruxton - the “jigsaw murders”. There were only seven hangings in 1936

Buck Ruxton - the “jigsaw murders”.

There were only seven hangings in 1936, but the one case really made the headlines that year was that of Dr. Buck Ruxton, which was one of the first instances of new forensic techniques playing a major role in securing a murder conviction in Britain.

Buck Ruxton was born Bukhtyar Rustomji Rantanji Hakim in Bombay, India on the 21st of March 1899. He qualified there as a doctor before emigrating to Edinburgh in 1927 where he took a post graduate course in medicine and in 1930 set up practice as a GP at 2 Dalton Square, Lancaster.

He changed his name by deed poll to Buck Ruxton around this time. Whilst in Edinburgh he had met and took as his common law wife, 34 year old Isabella Kerr whom he married in 1930 and the couple had three children. He was a popular young doctor in Lancaster. Their relationship was somewhat tempestuous as he was very jealous of her and accused her of having affairs. She had reported him to the police for assaulting her but it seems that no action was taken.

Isabella wanted to go to Blackpool for the illuminations and had arranged to meet her sisters there on Saturday the 14th of September 1935. It was not until the early hours of Sunday the 15th when she got home. Her prolonged absence led to another jealous quarrel later in the day, but on this occasion Ruxton strangled Isabella. The couple had a maid, 20 year old Mary Rogerson, who witnessed the murder and therefore was also killed.

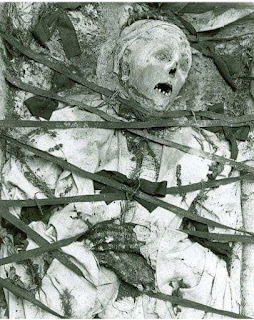

Ruxton decided to dismember the two bodies and remove all distinguishing marks from them. He dragged them to the bathroom and cut them up, wrapping the body parts in newspapers, pillowcases and sheets. These he took to Scotland on the night of the 19th of September and dumped them in to a ravine at "The Devil's Beeftub" near the town of Moffat, in Dumfriesshire.

He was observed loading the parcels into the car. On the journey home from Moffat he had knocked a cyclist off his bicycle in Kendal. The cyclist got the car’s registration number and reported the hit and run incident to the police. Kendal Police contacted Milnthorpe Police, who put up a road block at Milnthorpe where Ruxton was stopped and questioned and told to produce his driving licence and insurance to Lancaster police.

In the meantime Mary Rogerson’s mother had asked Ruxton where she was and been fobbed off with a story about her being pregnant and having been sent away to have the baby. She didn’t believe a word of this. She therefore reported her daughter missing to Lancaster police. Isabella was also reported missing by her family and the police questioned Ruxton about both disappearances but, as he was a doctor, they accepted his stories. He claimed that Isabella had left him for a new boyfriend.

The bodies were discovered in Moffat by a tourist named Susan Johnson who saw what appeared to be a human arm sticking out of the River Linn. She immediately reported the grim find to the police. A thorough search of the area revealed more packages containing body parts. Initially the police were unsure how many victims there were. The parts were examined by John Glaister, Professor of Forensic Medicine and his assistant Dr Martin of Glasgow University and Professor of Anatomy, James Couper Brash of Edinburgh University.

They painstakingly reassembled the bodies in a case dubbed by the press as the “jigsaw murders”. A new technique of photographic superimposition was used, matching two in life photo transparencies of Isabella, taken by local photographer Cecil Thomas in 1934, to two photos taken in the same orientation of one of the skulls found.

The match was perfect. See photos. They also used forensic entomology to identify the age of maggots on the bodies to give an approximate date of death. The Glasgow Police Identification Bureau used new fingerprint techniques to help identify the bodies.

Ruxton was questioned and arrested on the 13th October 1935 and charged with Mary’s murder. He was formally charged with Isabella’s murder on the 5th of November and remanded on both counts. A key piece of evidence against him was the newspaper that the some of the parts had been wrapped in. It was a special edition of the Sunday Graphic dated September 15th, 1935 and only sold in Morcambe and Lancaster. A thorough search of 2 Dalton Square revealed a lot of blood stains.

His trial took place in Manchester before Mr. Justice Singleton from the 2nd to the 13th of March 1936. The prosecution team comprised J. C. Jackson K.C, Maxwell Fyfe and Hartley Shawcross, with the defence in the hands of Norman Birkett K. C., Philip Kershaw and Edward Singer. The prosecution decided to proceed on Isabella’s case first. Mr. Jackson told the jury that "it does not need much imagination to suggest what happened in that house. It is very probable that Mary Rogerson was a witness to the murder of Mrs. Ruxton and that is why she met her death."

He then outlined to the jury the injuries caused to the two women and that from the bloodstains inside the house that both murders had occurred on the landing at the top of the stairs, outside Mary Rogerson's bedroom. Jackson added: "Down the staircase, right into the bathroom, there are trails and enormous quantities of blood. I suggest that when she went up to bed that a violent quarrel took place, that he strangled his wife, and that Mary Rogerson caught him in the act and had to die also."

Professor Glaister presented compelling evidence that the remains found were those of Isabella and Mary. This was challenged by Norman Birkett, but to no avail.

The only witness for the defence was Buck Ruxton himself, who continued to deny his guilt and suggest that the evidence was entirely circumstantial. In his closing speech, Norman Birkett stated "how much of this case has been pure conjecture." He further challenged the identification of the bodies and suggested to the jury that "if you are satisfied of the fact that in the ravine on that day were those two bodies, identified beyond a shadow of a doubt, it does not prove this case." The jury took just over an hour to return a guilty verdict and Ruxton sort leave to appeal.

The appeal was heard in London by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Hewart, sitting with Justice du Parc and Goddard. Norman Birkett contended that Mr. Justice Singleton had mis-directed the jury. The appeal was dismissed on the 27th of April. The Home Secretary, John Allsebrook Simon, saw no reason for a reprieve and thus the execution was set for 9.00 a.m. on the 12th of May 1936.

Amazingly, a petition for clemency was got up and signed by some 10,000 people.

On the appointed day Ruxton was hanged at Strangeways Prison Manchester by Thomas Pierrepoint, assisted by Robert Wilson. Ruxton was 5’ 7 ½” tall and weighed 137 lbs, so was given a drop of 7’ 11” by Pierrepoint, leading to fracture/dislocation of the 2nd and 3rd cervical vertebrae, according the LPC4 form.

The police had to deal with a very large crowd of people who had gathered outside Strangeways on that Tuesday morning, including anti-death penalty protestor Violet Van de Elst who was heckled and booed and afterwards arrested and charged with obstruction for which she was later fined £3 by Manchester Stipendiary Magistrate Mr. Wellesly Orr.

On the Sunday after his execution, Ruxton’s signed confession was published in the News of the World. It was dated the 14th of October 1935, and said in part, "I killed Mrs. Ruxton in a fit of temper because I thought she had been with a man. I was mad at the time. Mary Rogerson was present at the time. I had to kill her."

Comments

Post a Comment