Amphibian Doomsday Fungus Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis Is ‘The Most Deadly Pathogen Known To Science’

Amphibian Doomsday Fungus Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis Is ‘The Most Deadly Pathogen Known To Science’

The insidious pathogen invades a frog's skin cells, and quickly begins multiplying. The animal's skin begins to peel off, and it grows weary, and dies — but not before spreading.

When scientists discovered a plague killing frogs all over the world, they were concerned. Unfortunately, the problem is far worse than they thought, as this amphibian fungus is now being called “the most deadly pathogen known to science.”

According to The New York Times, 41 scientists released the first global analysis of this fungal outbreak on Thursday. The Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis pathogen has been killing frogs for decades and is still underestimated as a threat.

Published in the Science journal, the research concluded that the populations of over 500 amphibian species have drastically decreased because of this fungal outbreak. A minimum of 90 species has already been presumed to have gone extinct since then — an estimate twice as much as previously thought.

“That’s fairly seismic,” said Wendy Palen, a biologist at Simon Fraser University and co-author of the commentary alongside the published study. “It now earns the moniker of the most deadly pathogen known to science.”

|

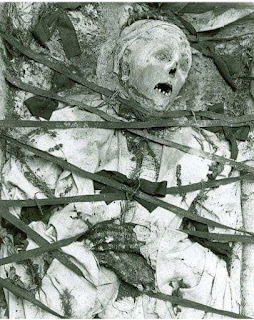

Wikimedia CommonsAn electron micrograph of a frozen, intact zoospore and sporangia of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis.

It was in the 1970s that scientists garnered the first inkling something was afoot: frog populations were rapidly declining, and nobody knew why. By the 1980s, some amphibian species had gone extinct. With fertile living conditions and largely supportive habitats, this was confounding.

In the 1990s, a clue finally emerged. Researchers discovered that frogs in both Panama and Australia were infected with a deadly fungus they named Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) — which started to turn up in other countries. DNA tests, however, pointed to the Korean Peninsula as its ground zero.

Scientists then discovered that amphibians in Asia were utterly impervious to Bd and that only once it reached other parts of the world did it begin to dangerously infect hundreds of vulnerable species. In terms of transportation, these frogs were likely victims of international animal trade and smuggling.

Exposure to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is both awe-inspiring and insidious. Infected amphibians spread the fungus by either direct contact or via spores floating in the water. It invades an animal’s skin cells — and multiplies quickly. Soon enough, a newly-infected frog’s skin will peel away. The animal grows weary, and dies — but not before spreading the fungus further by getting to new waterways.

In 2007, researchers began strongly considering the idea that Bd was responsible for all known and recorded declines of frog populations. While this comprised 200 species that had no other apparent cause of population decrease, scientists approached Bd methodically at the local level in specific species and places.

“We knew that frogs were dying all around the world, but no one had gone back to the start and actually assessed what the impact was,” said Benjamin Scheele, an ecologist at Australian National University and lead author of this latest study.

In 2015, Dr. Scheele and his colleagues collected the data of over 1,000 published papers on Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. They traveled the world to speak with experts on the pathogen and hear their theories — many of them unpublished — to garner some new, potentially valuable insight.

Dr. Scheele’s team even used museums in their research, finding Bd DNA in the preserved specimens stored in seemingly trivial storage cabinets. Their findings indicated that some frogs are at greater risk of contracting Bd than others and that the fungus is mainly found in cool, moist environments.

Dr. Scheele and his team identified 501 species in decline — a big leap from the previously established estimate of 200. Perhaps most notably in terms of frog population decline was the discovery that climate change or deforestation weren’t the biggest cause — Bd was.

“A lot of those hypotheses have been discredited,” said Dr. Scheele. “And the more we find out about the fungus, the more it fits with the pattern.”

This latest research into Bd has indicated that the pathogen likely wiped out plenty of amphibian species way before it was discovered. The unrecorded spread was only able to be estimated through Dr. Scheele’s idea of studying museum specimens and analyzing their DNA.

“It’s scary that so many species can become extinct without us knowing,” he said.

The 1980s marked the height of the theorized decimation of frog populations by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. This was a whole decade before researchers even observed or discovered the pathogen.

Currently, 39 percent of amphibian species that experienced population declines in the past are still undergoing it. Only 12 percent are showing signs of recovery — possibly natural selection opting for resistant animals over their vulnerable counterparts.

While this entire research project posits a fairly alarming and disconcerting future for our ecosystem, Dr. Scheele is surprisingly optimistic. In his mind, the main problem has been our lack of Bd awareness, all along. Now we can finally do something about it — and potentially change course.

“It wasn’t expected or predicted, and so it took the research community a long time to catch up,” said Dr. Scheele. “It’s just Russian roulette, with moving pathogens around the world.”

His argument has already been well-supported. In 2013, researchers discovered that a Bd-related fungus was threatening a population of fire salamanders in Belgium. The consequences would likely resemble those experienced by frogs — but Bd-aware scientists took action.

After conducting experiments, identifying the threat, and imposing barriers to certain trade that would facilitate the pathogen’s spread — the Belgium fungus was contained. It hasn’t posed a threat to a single other species anywhere in the world ever since.

“We’ve learned, and we’re dealing with it better,” said Dr. Scheele. “I guess the question is always, ‘Are we doing enough?’ And that’s debatable.”

Comments

Post a Comment