The massacre of the Isenschnibbe Farm: the fanaticism of the People and the scapegoat of the SS

The massacre of the Isenschnibbe Farm: the fanaticism of the People and the scapegoat of the SS

Where there is a crime, sooner or later, there is always also a scapegoat.

The ideal scapegoat is never innocent, because this mystification would not mislead anyone. The ideal scapegoat is ugly, dirty and bad. It is the personification of evil according to the mentality of his time.

Once upon a time, the ideal scapegoats were the "monsters", deformed people with a repulsive appearance. The well-known pathologist Pierluigi Baima Bollone, in "The last days of Jesus" explains that much of what we know about the effects of the crucifixion we learned from the examination of the remains of a young Jew, found in 1968 inside one ossuaries found in a 1st century tomb in Giv'at ha-Mivtar, near Jerusalem.

An Aramaic inscription tells us that they belonged to a certain Yhvhnn, i.e. John. John died crucified in the same period narrated by the synoptic Gospels. While alive, Giovanni had an evident deformity of the face, a very pronounced hare lip. It is not known why he ended up on the cross.

In Milan, during the excavations for the S.Ambrogio underground station, the skeleton of a boy buried there at an unspecified time between 1290 and 1430 was found in another ancient cemetery. The boy's skeleton has some evident deformities, including the so-called "wormian bones".

But he did not die as a result of these, but as a result of the torture of the wheel, one of the most barbaric ways invented in the past to prolong the agony of those sentenced to death. Since it is not clear what crime a man so obviously disabled could have committed, the hypothesis has been made that he may have been the victim of a sort of "human sacrifice" during one of the many plagues of the time.

A team of historians and jurists examined the minutes of a long series of trials carried out in the United States during the twentieth century and ended with the death sentence, and subsequent execution, of the accused. It turned out that at least 892 of these were manifestly irregular and that the sentences were pronounced on the basis of non-existent or certainly false evidence, or in the absence of evidence solely on the basis of psychological pressure exerted on the juries.

All the inmates in question were poor people: vagrants, alcoholics, unemployed, often already prejudiced for other crimes, mostly black. In this regard, we recall the story of George Stinney Jr, one of the youngest sentenced to death in history.

And so, injustice is done, to the delight of those who are convinced that shedding the blood of others is the best way to wash their own filthy conscience.

But there are not only scapegoats in the judicial sense.

There are also those in the historical sense. And they take shape following the same pattern. The historical scapegoats are those who, because they have made all the colors, are also seen to be attributed what they have not done.

These are always embarrassing things to study and also to tell because, on a superficial reading, it may seem that revisionism is being done, that one is trying to rehabilitate criminals who deserve no mercy. In reality, things are not exactly like this: this kind of "revisionism" (always assuming that we can use this term) serves to nail to their responsibilities criminals who have not been outdone, but have always gotten away with it.

The Nazis, in this sense, are the perfect scapegoat.

No one who has a shred of personal dignity would risk putting his face to stand out in their favor. It takes a lot of courage to say, even today, "No, it was not the Nazis", even with no intention of rehabilitating them, just to restore historical truth.

Already Franco Giustolisi, after long and in-depth studies on the so-called "Cabinet of shame" (a cabinet of the Roman palace Cesi-Gaddi, seat of the Council of the Military Judiciary, in which, in 1994, the dossiers relating to 695 investigations were found for Nazi-fascist massacres, all deliberately covered up), stressed that one of the most probable causes of the cover-ups was that many of the worst atrocities attributed to the Nazis in Italy in the period 1943-45 actually appear to be the work of Italians.

Moreover, there are not even the occasions, especially in Eastern Europe, in which someone from the place, taking advantage of the presence of the Nazis, proceeded to "settle scores" with Jews or other minorities in danger.

And then there are also the Germans themselves, the civilians, those who officially were neither SS nor bloodthirsty fanatics. Those who, according to the official vulgate, knew nothing of concentration camps and labor camps, and perhaps in some cases it is also true. But many, on the other hand, had known everything for a long time and actively participated in the atrocities. But only in a few cases have they been discovered red-handed.

Now we will talk about the most important of these occasions.

We are in Gardelegen, a large rural town in the Altmark, about 35 km northwest of Magdeburg. It is April 15, 1945 and a patrol of US infantry from the 2nd Battalion, 405th Regiment, 102nd Division, is patrolling the surroundings of the city, which was occupied the previous day, without finding any resistance.

They do not meet anyone, the Germans are now well hidden and are careful not to get caught with weapons in hand. At a certain point, however, a human figure with a miserable appearance appears from the countryside. It is an emaciated young man who staggers forward and wears a striped uniform torn in several places. The Americans understand that they have nothing to fear, they reach it and feed it.

The young man, with difficulty, says his name is Edward Antoniak, that he is Polish and that he is 18 years old.

But how did he manage to reduce himself to that state?

He also says that something terrible happened, which he miraculously survived. The Americans don't seem so convinced and Edward offers to guide them there, gathering his last strength.

Following Edward, the Americans arrive at a brick structure, a large barn, outside the town.

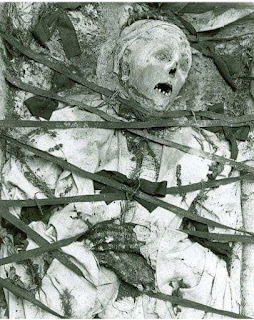

Around, there are ditches full of corpses, there are everywhere. Some are burned and almost unrecognizable. Others were shot dead and wearing uniforms with stripes identical to that of Edward.

The patrol raises the alarm. The commander of the 102nd, Major General Frank A. Keating, decides to go through with this matter. Photographers from the U.S. also arrive Signal Corps, which in the following days will document the spectacle of the many bodies that tell of atrocious deaths.

On April 19, the correspondents of the New York Times and the Washington Post send the first articles. In one of these, an interviewed American soldier says: “Before I had never been so sure of my reasons for fighting. Sometimes I thought the stories they told me were propaganda, but now I know that's not the case. I had never seen so many deaths before ”.

While the corpses are counted, which will turn out to be 586 outside the barn and 430 inside, the investigations lead to disconcerting conclusions. To kill so many people, the Nazis would have had to be so many too. Instead, there is no trace of the SS or of their recent passage. Whoever carried out that massacre did not leave Gardelegen.

Everything indicates, in fact, that it was the same inhabitants of the country.

The Americans are furious and, without too many compliments, forcefully take about 300 German civilians from their homes and order them to immediately arrange for the burial of the bodies. To the timid objections of the Germans, who declare themselves unrelated to the fact, Colonel George Lynch responds harshly:

“The German people have been told that the stories of atrocities committed by the Germans were the exclusive fruit of our propaganda. You now say that only the Nazis are responsible for this horror. Talk about the SS, the Gestapo. The responsibility for this crime is not theirs, it is yours. Your so-called superior race has proven to be superior only in crime, cruelty and sadism. You have lost all respect from the human race ”.

There is also a singular detail to nail the inhabitants of Gardelegen. The Germans surrendered even before the Americans arrived, the military contingent defending the city fled without a trace. It happened in fact that a US prisoner, Lieutenant Emerson Hunt, captured while he was on patrol, just brought to the German command, invented a story that, when they took him, he was trying to reach the city to deliver a message containing the request to surrender, otherwise the overwhelming American forces would have wiped out everything.

The German officers believed it and ran away, without even trying to improvise a defense. The Americans marveled at being able to enter Gardelegen so quickly and easily. But this also blew up the plans of those who were convinced they had enough days ahead of them to get rid of all the corpses, burning them.

The Americans instruct Lieutenant Colonel Edward E. Cruise, investigative officer of the War Crimes Section of the Ninth Army, with the official investigation into the facts.

The conclusions of Cruise's investigation will be as follows.

The 1016 dead were all prisoners of war and deportees, of Polish, Soviet, French, Hungarian, Belgian, Italian, Czechoslovakian, Yugolslav, Dutch nationality. There were even Spaniards and Mexicans. Some were Germans like their killers. They belonged to a group of 1027 who represented a fraction of those engaged in one of the infamous "death marches" with which the Germans tried to remove prisoners, deportees, hostages and forced labor from the front line, both to continue exploiting them and to eliminate them before they could reveal the crimes they had witnessed.

Those who ended up in Gardelegen had been detained, until April 4, in the concentration camp of Mittelbau-Dora, near Nordhausen, in Thuringia. There, after the bombing of Peenemunde, the production of V1 and V2 missiles had been moved. About 40,000 had left Mittelbau-Dora, initially by train, headed for the fields of Bergen-Belsen, Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme; but many of them, already severely tested by the life of the camp, had died along the way, often killed by the overseers because they could hardly walk, after being forced to proceed on foot due to the damage caused by the bombing of the railway lines.

It had taken several days to completely evacuate the camp, in which about 20,000 deportees had died of starvation and disease during the period of activity. The task was made more difficult by the limited number of men available: the SS, who were relatively few, had enlisted as auxiliaries, wherever they happened, anyone who seemed remotely skilled in the service: firefighters, airport personnel who were unemployed following the destruction of the air fleet, members of any other organization and especially several teenagers of Hitlerjugend.

A column of sealed wagons had reached Meiste station, near Gardelegen, on 13 April, after which it was impossible to continue by train. Before continuing on foot, the overseers had decided to abandon all those who appeared to be in worse condition. There were too many to be eliminated without wasting too much time, so they had given them to the local population.

In Gardelegen there were very few SS men but, on the other hand, the civilians had immediately joined them. In the general chaos, as soon as the wagons opened, the prisoners, who had not drunk for days, threw themselves into the water of the puddles and ditches to quench their thirst with it. Then, they started picking up anything vaguely edible from the ground and eating it raw.

Some had managed to break into a grain warehouse and were shot dead.

The English journalist Karel Margry, of the specialized magazine "After the Battle", studied all the documents of Cruise's investigation and states that, initially, a minority of Gardelegen inhabitants, pitying the state of the deportees, tried to hide some of them in the barns and in the stables. But most Germans saw in these skeletal men a threat to their own survival. Most of the prisoners who tried to escape were captured by zealous civilians, not the SS.

It seems that someone had told a story, certainly made up, about a group of escaped prisoners who had devastated a nearby village and killed all its inhabitants. The conditions of the prisoners were not enough to reassure the Germans, who were terrified of the idea of ending up in the same way.

Instead the prisoners were calm. They heard the sounds of battle getting closer and thought that soon they would be released. Some were elated, having managed to fix a few potatoes and turnips which, while eaten raw, were their best meal in years.

The Germans, among whom there were very few SS and very many civilians, decided to concentrate them in one place and eliminate them all. The best place seemed to be the large brick barn of the agricultural estate called Isenschnibbe, about 2 km from the city.

The prisoners allowed themselves to be led there without resisting, convinced that, hospitalized there, if nothing else, they would not have spent another cold night outdoors. Those who were unable to walk fast enough were carried in chariots.

In less than 24 hours, on April 14, the Americans would have entered the city.

When they had closed all the prisoners in the barn, the Germans tried twice to set the straw on fire, first by throwing inside rags soaked in gasoline and ignited and then firing signal flares at it. In both cases, the prisoners managed to put out the fires before they spread.

A group of Russian prisoners forced open one of the doors and managed to get out. The Germans lost their minds. There were some disbanded soldiers, especially paratroopers, and young people from the Hitlerjugend, armed with machine guns: they started shooting madly, cutting down everyone who came out.

Finally the Germans managed to set fire to the barn.

A Polish prisoner, Mieczystan Kotodzieski, managed to escape from one of the doors without being hit. Three other prisoners managed to dig a passage between the floor and the wall of the barn and exited from there. Seven other prisoners, including Edward Antoniak, scrambled up the barn beams, covering their faces with urine-soaked rags to protect themselves from the smoke.

The others almost all died in the fire. Those who didn't die right away were shot down by the Germans, who came in to check, when the flames went out. It was now dawn on April 14th.

The 11 survivors were 7 Poles, 3 Russians and 1 French.

The Americans forced the inhabitants of Gardelegen to dig the graves for all 1016 dead and put white crosses on them. A countryside area was used as a cemetery for the victims and a monument was erected in their memory. Before leaving, the Americans placed a plaque at the entrance to the cemetery, warning the inhabitants to always keep it in perfect condition so that it would remain as a warning against war and fanaticism.

However, good intentions remained on paper, also because Gardelegen was part of East Germany for a long time. The perpetrators of the crime themselves have never been identified with certainty.

It was easy only to capture and nail the local SS leader, Erhard Bruny, who was tried and sentenced to life in prison and died in prison in 1950.

Instead, the major perpetrator of the crime got away with it, incredibly. His name was Gerhard Thiele and he was the local "Kreisleiter" (senior Nazi party official). The clues as to who ordered all prisoners to be killed point straight to him, according to research by historian Daniel Blatman.

But, while Lieutenant Colonel Cruise was conducting his investigation, Thiele had already melted. When he saw that the soldiers were fleeing, he had exchanged his pompous uniform with that of a dead soldier and had assumed his identity, joining the flight. Later, the division of the two Germanys led to forget the Gardelegen affair and Thiele was able to take his name again, without anyone being able to connect him to the role of Kreisleiter. It seems that, by passing himself off as a prisoner soldier and managing to exploit his good knowledge of English, he also managed to be employed as an interpreter by the occupation forces, obtaining special treatment.

He lived the rest of his life in West Germany and died in 1994, aged 83.

The cemetery and the monument still exist, despite everything. British journalist David Young of The Mirror visited them in 2016, finding them not quite in a state of neglect, but sloppily kept. He returned there in 2019 and found that a new visitor center was under construction, after some associations active in the preservation of Holocaust testimonies had taken the site to heart.

In Italy, of this story, very little has arrived, almost nothing. Someone is aware of this only because the German writer Harald Gilbers, author of a series of novels starring the Jewish policeman Richard Oppenheimer, set in the 1940s, was inspired by this story for a novel called "The Black List", translated into Italian by the publisher Emons.

Comments

Post a Comment