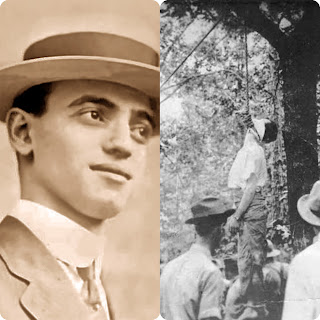

Abduction and lynching of Frank

Abduction and lynching of Frank

The June 21, 1915 commutation provoked Tom Watson into advocating Frank's lynching.[201] He wrote in The Jeffersonian and Watson's Magazine: "This country has nothing to fear from its rural communities.

Lynch law is a good sign; it shows that a sense of justice lives among the people." A group of prominent men organized themselves into the "Vigilance Committee" and openly planned to kidnap Frank from prison.

They consisted of 28 men with various skills: an electrician was to cut the prison wires, car mechanics were to keep the cars running, and there was a locksmith, a telephone man, a medic, a hangman, and a lay preacher.

The ringleaders were well known locally but were not named publicly until June 2000, when a local librarian posted a list on the Web based on information compiled by Mary Phagan's great-niece, Mary Phagan Kean (b. 1953).

The list included Joseph Mackey Brown, former governor of Georgia; Eugene Herbert Clay, former mayor of Marietta and later president of the Georgia Senate; E. P. Dobbs, mayor of Marietta at the time; Moultrie McKinney Sessions, lawyer and banker; part of the Marietta delegation at Governor Slaton's clemency hearing; several current and former Cobb County sheriffs; and other individuals of various professions.

On the afternoon of August 16, the eight cars of the lynch mob left Marietta separately for Milledgeville. They arrived at the prison at around 10:00 p.m., and the electrician cut the telephone wires, members of the group drained the gas from the prison's automobiles, handcuffed the warden, seized Frank, and drove away.

The 175-mile (282 km) trip took about seven hours at a top speed of 18 miles per hour (29 km/h) through small towns on back roads. Lookouts in the towns telephoned ahead to the next town as soon as they saw the line of cars pass by. A site at Frey's Gin, two miles (3 km) east of Marietta, had been prepared, complete with a rope and table supplied by former Sheriff William Frey.

The New York Times reported Frank was handcuffed, his legs tied at the ankles, and that he was hanged from a branch of a tree at around 7:00 a.m., facing the direction of the house where Phagan had lived.

The Atlanta Journal wrote that a crowd of men, women, and children arrived on foot, in cars, and on horses, and that souvenir hunters cut away parts of his shirt sleeves. According to The New York Times, one of the onlookers, Robert E. Lee Howell – related to Clark Howell, editor of The Atlanta Constitution – wanted to have the body cut into pieces and burned, and began to run around, screaming, whipping up the mob.

Judge Newt Morris tried to restore order, and asked for a vote on whether the body should be returned to the parents intact; only Howell disagreed. When the body was cut down, Howell started stamping on Frank's face and chest; Morris quickly placed the body in a basket, and he and his driver John Stephens Wood drove it out of Marietta.

In Atlanta, thousands besieged the undertaker's parlor, demanding to see the body; after they began throwing bricks, they were allowed to file past the corpse.

Frank's body was then transported by rail on Southern Railway's train No. 36 from Atlanta to New York and buried in the Mount Carmel Cemetery in Glendale, Queens, New York on August 20, 1915.

(When Lucille Frank died, she was not buried with Leo; she was cremated, and eventually buried next to her parents' graves.) The New York Times wrote that the vast majority of Cobb County believed he had received his "just deserts", and that the lynch mob had simply stepped in to uphold the law after Governor Slaton arbitrarily set it aside.

A Cobb County grand jury was convened to indict the lynchers; although they were well known locally, none were identified, and some of the lynchers may have served on the very same grand jury that was investigating them.

Nat Harris, the newly elected governor who succeeded Slaton, promised to punish the mob, issuing a $1,500 state reward for information.

Despite this, Charles Willis Thompson of The New York Times said that the citizens of Marietta "would die rather than reveal their knowledge or even their suspicion [of the identities of the lynchers]", and the local Macon Telegraph said, "Doubtless they can be apprehended – doubtful they will."

|

| Leo Frank's lynching on the morning of August 17, 1915. Judge Morris, who organized the crowd after the lynching, is on the far right in a straw hat. |

Several photographs were taken of the lynching, which were published and sold as postcards in local stores for 25 cents each; also sold were pieces of the rope, Frank's nightshirt, and branches from the tree. According to Elaine Marie Alphin, author of An Unspeakable Crime: The Prosecution and Persecution of Leo Frank, they were selling so fast that the police announced that sellers would require a city license.

In the postcards, members of the lynch mob or crowd can be seen posing in front of the body, one of them holding a portable camera. Historian Amy Louise Wood writes that local newspapers did not publish the photographs because it would have been too controversial, given that the lynch mob can be clearly seen and that the lynching was being condemned around the country.

The Columbia State, which opposed the lynching, wrote: "The heroic Marietta lynchers are too modest to give their photographs to the newspapers." Wood also writes that a news film of the lynching that included the photographs was released, although it focused on the crowds without showing Frank's body; its showing was prevented by censorship boards around the U.S., though Wood says there is no evidence that it was stopped in Atlanta.

References

- Wikipedia-Leo frank

- "The modern historical consensus, as exemplified in the Dinnerstein book, is that ... Leo Frank was an innocent man convicted at an unfair trial."

- A 1900 Jewish newspaper in Atlanta wrote that "no one knows better than publishers of Jewish papers how widespread is this prejudice; but these publishers do not and will not tell what they know of the smooth talking Jew-haters, because it would widen the breech [sic] already existent."

- Dinnerstein wrote, "Men wore neither skullcaps nor prayer shawls, traditional Jewish holidays that the Orthodox celebrated on two days were observed by Marx and his followers for only one, and religious services were conducted on Sundays rather than on Saturdays."

- Lindemann writes, "As in the rest of the nation at this time, there were new sources of friction between Jews and Gentiles, and in truth the worries of the German-Jewish elite about the negative impact of the newly arriving eastern European Jews in the city were not without foundation."

Comments

Post a Comment